Equinoxes and Solstices

- 17th Mar 2022

- Author: Catherine Muller

As Earth makes its yearly trip around the Sun and the amount of daylight we get each day gradually changes it can be difficult to pinpoint exactly when we transition from one season into the next. However, there are four days on the astronomical calendar, two equinoxes and two solstices, that officially mark these transitions. Known since antiquity, these important days have been celebrated by many ancient civilisations.

The Seasons

But why do we have seasons at all? To answer this, we need to consider Earth’s rotational axis – an imaginary line running from the North to the South Pole. Although the Earth spins around this axis roughly every 24 hours to give us night and day, the seasons are produced because this axis is not upright, it is actually tilted at an angle of 23.5°. So as the Earth orbits the Sun throughout the year, the hemisphere tilting towards the Sun continually changes. We can expect longer days in the hemisphere that is tilted towards the Sun, where it will be summer, whilst it is winter in the hemisphere that is pointed away.

Earth’s orbit around the Sun isn’t perfectly circular, it’s an ellipse. This means we’re not always the same distance away from the Sun. In fact, Earth is closest to the Sun in January. You might expect us to have summer then, but in the Northern Hemisphere we have winter. This proves that the tilt of Earth’s axis is the main influence on the seasons.

Equinoxes

There are, however, two points in the year when it is neither the North Pole nor the South Pole that faces towards the Sun, and the Sun instead lies over the equator. These are called the equinoxes, from the Latin words aequus (equal) and nox (night). As the name suggests, on the equinoxes, day and night are of roughly equal length everywhere on Earth’s surface.

The date of the equinoxes can shift each year but always fall around or on 20 March and 22 September. The March equinox signals the beginning of spring in the Northern Hemisphere (it is sometimes referred to as the vernal equinox) and the beginning of autumn in the Southern Hemisphere. In September, the opposite occurs, when the equinox marks the beginning of autumn in the northern half of the Earth and the beginning of spring in the southern half.

We have the equinoxes to thank for certain events throughout the year. For example, the Harvest Moon is the full moon that falls closest to the autumnal equinox. Additionally, Easter Sunday is defined as the first Sunday after the full moon that falls closest to the spring equinox! (So, if the full moon falls on a Sunday itself, then Easter is the next Sunday). This also explains why the date of Easter changes each year.

Solstices

The two solstices occur approximately midway between the equinoxes, in June and December. These are the points in Earth’s orbit when the Earth’s rotational axis is at its maximum tilt towards or away from the Sun. For example, in the Northern Hemisphere, the summer solstice happens around 20/21 June when the North Pole points directly towards the Sun. As a result, everyone in the Northern Hemisphere experiences the day in the year with the longest hours of daylight. This marks the beginning of summer. Conversely, in the Southern Hemisphere, where the South Pole is tilted away from the Sun, it is the beginning of winter, and they experience the day with the shortest hours of daylight.

The opposite is true of the December Solstice, which falls around 21/22 December. On this solstice, the South Pole is tilted towards the Sun, and the North Pole away. As a result, the Northern Hemisphere experiences the shortest hours of daylight on this date marking the beginning of winter, whereas the Southern Hemisphere sees the start of summer with the longest hours of daylight in a day. So, while many of us in the UK are celebrating Christmas indoors shielding from the cold and darkness outside, South Africans would be enjoying a Christmas barbeque on the beach!

Celebrating the Equinoxes and Solstices

The Sun’s path across the sky is something that has been tracked by civilisations throughout history. We can see evidence of this around the world in the form ancient monuments that mark the equinoxes or solstices.

For example, at the Temple of Kukulcán, a step pyramid in Mexico, a shadow shaped like a serpent appears to descend the pyramid at both equinoxes. And at Stonehenge, a prehistoric monument of standing stones in Wiltshire, England, the solstices are celebrated. On 21 June, the Sun rises behind one of the stones and perfectly into the heart of the monument, ushering in the summer.

As people still flock to these sights thousands of years later to celebrate the changing of the seasons, it is clear the equinoxes and solstices are some of the most special astronomical events throughout the year.

Full references / credits:

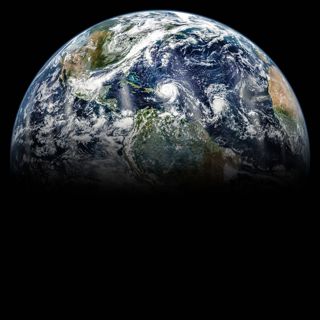

(Banner) Earth with hurricanes over the Atlantic. Credit: NASA/Joshua Stevens

(1) Earth tilt animation. Credit: Tfr000 CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Earth_tilt_animation.gif)

(2) Equinox / Solstice. Credit: NOAA

(3a) Winter Solstice. Credit: Przemyslaw "Blueshade" Idzkiewicz CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Earth-lighting-winter-solstice_EU.png#/media/File:Earth-lighting-winter-solstice_EN.png/2)

(3b) Summer solstice. Credit: Przemyslaw "Blueshade" Idzkiewicz CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Earth-lighting-summer-solstice_IT.png#/media/File:Earth-lighting-summer-solstice_EN.png)

(4) Stonehenge Solstice. Credit: Andrew Dunn CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Summer_Solstice_Sunrise_over_Stonehenge_2005.jpg)