How did the Planets get their Names?

- 10th Feb 2025

- Author: David Southworth

Most of you reading this are probably well aware of the names of the planets in our Solar System, and their broad origin as the names of Roman or Greek gods. But how was each planet assigned to a god, how did this influence the naming of our days of the week and what approach have other languages and cultures taken?

The origin of Western names for the planets

In Ancient Greece the planets were not named directly for gods. Rather they were given names broadly representing their characteristics. Each planet was also assigned as sacred to a particular god, again often based on characteristics.

Stilbon, or “the gleamer”, was the fastest planet across the night sky, so was assigned to Hermes, the messenger of the gods. Phosphoros, “the light bringer”, was the name for the brightest planet, assigned to Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Pyroeis, “the fiery”, named for its gentle red hue, was ruled over by Ares, the god of war. Phaethon, “the bright”, was assigned to Zeus, the king of the Olympian gods. And finally Phainon, “the shiner,” as the slowest or most stately planet across the sky, was sacred to Cronus, the leader of the Titan gods and father of Zeus.

The Romans, influenced by Greek traditions and learning, took the Greek gods associated with each planet and gave those planets the names of the equivalent gods in their own pantheon – Mercurius, Venus, Mars, Iuppiter, and Saturnus. These names subsequently made their way, with only minor variations, into most modern European languages.

The invention of the telescope in the early 17th century paved the way for the discovery of more distant, fainter planets and the convention of using names of ancient gods was continued. The seventh planet, discovered in 1781, was eventually named after the Greek god of the sky, Ouranos. Just as Cronus (Saturnus) was the father of Zeus (Iuppiter), so Ouranos was the father of Cronus. It’s thought that the Greek name was adopted in error, with the assumption that the Latinised form Uranus would be the Roman version, although the equivalent Roman god is actually Caelus. In subsequent centuries, Neptune, the Roman god of the sea, was adopted for the eighth planet, and Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld, for what was then considered the ninth.

A link with the days of the week

The names of the planets can also be seen in the days of the week in many European languages. There was a belief among some in Ancient Rome that the five known planets, plus the Sun and Moon, took turns watching over the Earth.

The days of the week then took their names from the celestial body that was on watch at the start of that day. The way the timings of these shifts worked out led to the order being as follows – Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Saturn.

These links are still present very clearly in the names Sunday, Monday and Saturday, and more indirectly in the names of the other days in English, which come from the Norse gods with broad equivalence to those Roman gods – Tiw, Woden, Thor and Frigg respectively.

In most Romance languages, the link is even more direct. Although the naming of the weekend days has changed over the years, the remaining days refer directly to those planets. For example, in Italian, we see lunedi (from la Luna – the Moon), martedi, mercoledi, giovedi (Jove is an alternative name for Jupiter), venerdi and sabato. In French, we have lundi, mardi, mercredi, jeudi, vendredi and samedi.

Planet names in some other traditional cultures

The two approaches seen above, of naming planets in honour of gods or to be broadly descriptive, are replicated in many other cultures.

For example, traditional Hebrew astronomy took an approach much like that of Ancient Greece, with the planets’ names being descriptive, or representative of that planet’s supposed influence in the culture. Mercury is known as Kokhav, simply “the planet” intended to represent a blank slate allowing adaptability. Venus is Nogah, “the bright one”, and Mars Ma’dim, “the red one”. Jupiter’s name, Tzedek, means “righteousness” or “justice”, with the planet thought to embody the divine. Saturn is named Shabtay, meaning “of the Sabbath”, interestingly tying in with the naming of Saturday in Western cultures. The approach also extends to the Sun – Khamma, or “the hot one” and the Moon – Levana, or “the white one”.

Traditional Persian naming is an example of a system honouring local gods, generally tying in with the equivalent Greek and Roman gods. This gives us Tir for Mercury, Nahid for Venus, Bahram for Mars, and Hormoz for Jupiter. Saturn, however, is named differently, its name Keyvan coming from the ancient language of Akkadian. The name means “steady”, as in the Ancient Greek system, acknowledging its slow movement across the sky. When Uranus, Neptune and Pluto were discovered, modern Persian borrowed those words almost precisely from the Western names.

The approach of Chinese philosophy

An interesting approach can be found in the Chinese names for the planets. These tie in with the much broader disciplines of Chinese philosophy, known as Wuxing. This is hard to translate accurately, but is usually referred to as the Five Phases or Five Elements. In this system, the five elements in question interact with each other and can be thought of as requiring balance between them. They are thought to relate to various aspects of culture and life, with each of the five having an association with a wide range of properties, including colours, emotions, senses, particular movements in martial arts such as tai chi, parts of the body, and indeed planets.

This gives the planets names with the following meanings – Mercury is “the water star”, Venus is “the metal star”, Mars is “the fire star”, Jupiter is “the wood star” and, somewhat confusingly from an anglophone perspective, Saturn is “the earth star”!

Traditional Chinese influence over the region means that the same or similar names have also been adopted in other East Asian languages, including Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese. The names for the outer planets have again been based on the western names but, in this instance, in translation from the roles of the gods in question, rather than adopting the words themselves. So Uranus became “the Heavenly King star”, Neptune “the Sea King star”, and Pluto “Star of the King of the Underworld”.

Full references/credits

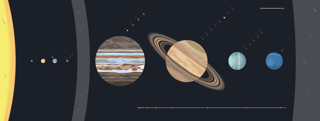

(1) A diagram of the Solar System. Credit: Torr3 (CC BY-SA 4.0 - https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/)

(2) The planet Mercury, originally named after the messenger of the Greek gods, because of its fast movement through the sky. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington (Public domain)

(3) A Roman copy of a bust of Zeus, after which the planet Jupiter was originally named. The Italian name Giove can be seen at the base. Credit: Unknown artist (Public domain)

(4) A 19th Century Persian astronomical diagram. Credit: Christies.com (Public domain)

(5) A diagram of the interaction of the elements of Wuxing. Credit: Parnassus (CC BY-SA 3.0 - https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)